Monday 28 July 2025

Ask, give, and receive feedback

Whether written on a sticky note, left as a Figma comment, or said IRL, feedback is an essential aspect of UX design.

No UX designer succeeds without feedback from peers, leads, developers, researchers, even the folk whose feedback is most critical of all: users. Yet, it can be tricky to master the soft art of feedback. It requires a kind of malleability and directness when asking for it, giving it, and receiving it.

I’ve mentioned before how feedback on creative output can have a specific kind of sting. Designers care a great deal about their work, sometimes to a fault, so receiving feedback can be subtly and overtly avoided and internalised.

Feedback can be hierarchical

I have a theory. The more abstract, technical, or out-of-reach a craft is, the “harder” it is to give feedback.

I don’t remember the last time a product manager reviewed a developer’s codebase and left feedback on the solution or structure. I also don’t recall ever giving feedback to a director on their strategy.

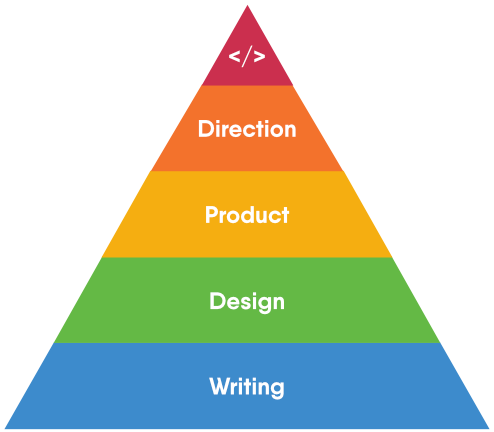

My 'Ease of feedback hierarchy' pyramid

When everyone can read and write and most can see and have visual preferences, the “easier” it is to give feedback, so design and writing tends to be that “easier” feedback to give. Of course, take this with a pinch of salt but it was a realisation that helped me understand why there seems, at times, to be so much feedback on my work.

Feedback is nuanced

It can also be tempting to think of feedback in purely black and white terms: good or bad, constructive or unhelpful. But feedback is a bit more nuanced than that.

The best kind of feedback is always constructive, even seemingly “negative” feedback. The worst you want to hear, and give, is unhelpful and negative feedback.

| Positive | Negative | |

|---|---|---|

| Constructive | “This supporting info is contextual and helps address the user pain point.” | “This supporting info doesn’t include the correct terminology.” |

| Unhelpful | “Great job, love it!” | “I’m not impressed with your work.” |

I was once on the receiving end of the “I’m not impressed with your work.” feedback. What a way to help someone improve, especially when it wasn’t followed up with anything at all constructive.

The best thing to keep in mind though is 99.999% of the time, people mean well when giving feedback; no matter the amount, the content, or the way it’s given.

So here are some assorted tips to practice the soft art of UX feedback. They’re not absolute or essential at all times. Think of them as a mindset or tools to help you make the best work you can.

How to ask for feedback

First of all, never, ever ask anyone, “What do you think?” You’ve essentially created a Rorschach test and possibly wasted their time and yours.

Generic questions generate generic responses. Instead, ask revealing questions.

- Which of these variants is easier to understand?

- What other ways could this be solved?

- What other essential information is needed?

- Does the placement of this feature make sense?

- Does this solution help users achieve x, y, z?

- Would a new user be able to use this without x, y, z?

Think like a researcher and utilise those who, what, where, etc. questions. And yes, yes-no questions are valid, just make sure to frame the question to elicit the response you need.

Size your feedback. If you’re changing something as small as an icon, chances are you don’t need to ask for feedback.

On the extreme end of this imaginary spectrum, if you’re designing an entirely new product or procedure that every user will interact with, you’ll absolutely need feedback from everyone involved on whatever you create.

Somewhere in the middle? Component variants? Adjusting small page sections? Check in with those that need to know.

Time your feedback and be realistic with others’ time. Avoid ‘too little, too early’ like seeking feedback on a low-fidelity concept before the project is even on the team roadmap.

Avoid ‘too much, too late’ like one week before developers are ready to start, asking a lead designer to review a full end-to-end prototype, with everything “signed off” by product managers.

You always want to ask for feedback early in the process, as well as that Goldilocks moment like conducting a UX crit after a few concept drafts.

How to give feedback

Word police alert! Just say what you want to say.

No need to overcook, explain, or engineer what you want to mean.

Instead of a whole paragraph or three minutes explaining the intricacies of a similar feature that you worked on and the back and forth it required with other departments and aligning with the design systems team and creating tickets and Slack messages… Just say, “I used this icon instead.”

Save your time, and theirs.

Balance feedback. I have a tendency to focus a little too much on the positive aspects when giving feedback; I don’t want to upset anyone (I’m also doing them a disservice). And when I seemingly receive more “negative” feedback than “positive”, I wonder if my work is ever good enough.

It’s important to ask for balanced feedback as much as give it freely. Check if you tend to only give positive or negative feedback. Ensure it’s always constructive, and try balancing it.

There’s always room for improvement, and there’s always something that’s working. Help your colleagues see the difference.

Is it feedback or a question? You decide! Figure out if you’re asking a question or pointing something out. Avoid mixing the two. Questions are always to be encouraged, but sometimes:

| Feedback like this… | …makes me think. |

|---|---|

| “I wonder if there’s another way to solve this?” | “Is there? What is it? Or do you not think this solution works?” |

| “Have you thought of a different action here?” | “Not really, but why are you asking?” |

| “Is this confusing?” | “Is it? You tell me!” |

If you think something is confusing, say it! You’ll help me and the end user out more if you use your words.

How to receive feedback

Thank you, thank you, thank you at all times. Practice acceptance. Someone else’s opinion or feedback is just that, their opinion or feedback. No need to defend or argue it. It can be tempting to disagree if it’s something really subjective. The worst you can be is confrontational.

| When this feedback is given… | …avoid reacting like this. |

|---|---|

| “This could work as radio buttons instead of buttons.” | “You’re wrong! I’m the designer. I know better.” |

| “This sentence reads a little clunky. Can it be shortened?” | “No.” |

| “The default view of tables with this kind of data is 10 rows.” | “Well this table is different because of reasons x, y, z.” |

Yikes. Don’t be that guy. I’ve worked with that guy. And I hate to admit it, sometimes I’ve been that guy. Thank the person, especially if you disagree. It’ll soften the blow, and you might actually come to see, they have a point.

Speaking of having a point, count them. Did one person say it, or one hundred? Stating the obvious, but the more people say something is positive or negative, the more it tends to be true. But remember, one person can hit the nail so on the head you might facepalm and wonder how you could have omitted something so simple or critical.

And yet, every team member might think three steps instead of two is overdoing it, but you have to include step three for a regulatory or legal reason (for example).

And “worst of all” if you get a near 50/50 split of constructively positive and negative feedback, then use your best judgement or check with key stakeholders what to do!

All of this is to say

Accepting ≠ agreeing. Actively seek feedback out, and accept all of it. It doesn’t mean you have to agree with all of it. Not all feedback is necessary, but all feedback should be reviewed and considered.

Feedback for the sake of feedback isn’t useful feedback either. Always assume good intentions as much as you can. Remember, sometimes, people just like to be heard or feel like they're contributing. Learn to spot the kind of feedback you’re receiving, and giving.

| The ‘do as I say’ feedback | The ‘I know more than you’ feedback | The ‘splitting hairs’ feedback |

|---|---|---|

| “This approach won’t work. I can’t explain why.” | “That’s not how users behaved when we tested it.” | “It was actually 17.2%, not 17.1%.” |

| “Change it.” | “That’s not how I would do it.” | “That blue isn’t blue enough.” |

Just do it. Asking, giving, and receiving feedback is a skill. Practice it. We don’t learn by always getting things right the first time, or working in a vacuum.

Your work is what you’re looking to improve, not your ego.